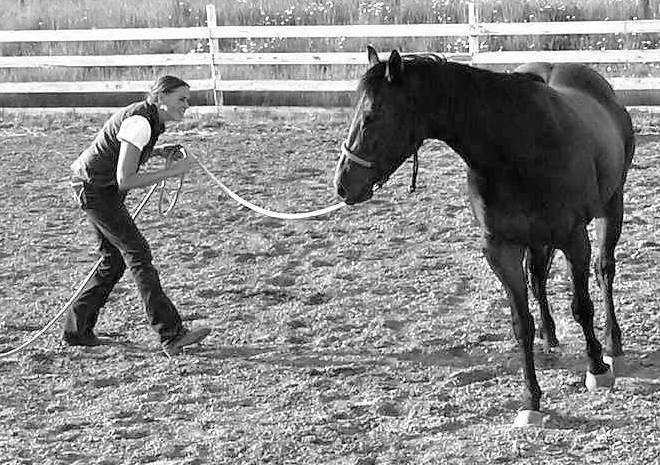

Kyla puts a first ride on a young horse

Editor’s Note: Kyla Strange is a talented Canadian horsewoman with followings in British Columbia and New Brunswick. She’ll be a Special Guest at the Best Horse Practices Summit in Maine in October.

Strange has started colts, competed, and been featured in Eclectic Horseman. Her mentors include Jonathan Field, Ray Hunt, Martin Black, and many others.

In this essay, she reflects on the challenging mission of intent.

Kyla writes:

I’m reflecting on a young mare I was starting her under saddle. She was a running quarter horse, bred specifically for competitive barrel racing. Round in stature, solid throughout, with lots of reserve from months on pasture grass. She had big doe eyes and a gorgeous, dark liver sorrel sheen of a summer coat.

The first thing she taught me was that she hadn’t had a lot of great human handling before coming to me as a four-year-old.

When I first started working with her, she shared that she was very difficult to lead safely on a line from Point A to Point B. She was a fire-colored kite at the end of a string on a very windy day. She would frighten easily and she follow her natural instinct to flee from suspected dangers. She would get straight and strong and bolt, putting the human in imminent danger of bad rope burns and oodles of sand skiing.

Kyla works with a young horse

First, I helped her understand that being in my personal space was a very uncomfortable place for her to be. I establish this immediately with all new-to-me horses because it fundamentally will keep me safe. I don’t get mean or mad. I make it as uncomfortable as I need to for the horse to get the message.

Essentially, I help the horse seek the comfort inside its own skin, in a place that is away from me, not on top of me. It’s okay, of course, to invite the horse into my space for the best belly scratches on earth and to build undemanding rapport. Being close is also required for practical things like brushing, tacking up, mounting, etc.. But I avoid the temptation to shelter them from danger.

In so many round pens today, there is the infamous Join Up. The human draws the horse in, in, in. The inexperienced hand forgets to help the horse, to support the horse, so the horse can gain confidence in its own right, on its own four feet, away from its human.

Fundamentally, my goal is to find balance in the draw and the ‘Hey, friend. You are ok over there. You are safe and comfortable on your own. Over there. Brave, smart, capable you. Yes, over there, the not-on-top-of-me place.’

The balance between the draw and the Feel Good Over There is key. It’s also critical to effectively ask a horse to back up straight with the slightest request.

This accomplishes many things:

This accomplishes many things:

- You engage the horse’s feet which, in turn, engages their mind.

- The horse gets in a learning frame of mind.

- The horse can respond in a hurry, but without too much chaos or misunderstanding.

- The horse really has to ‘think’ to back up straight. A lot of horses get locked up when asked to back, often more mentally more than physically. But then I see these horses after they back up a few steps, lick their lips profusely and get more calm and relaxed. Through this manifestation, it’s like the horse is saying, ‘Thanks, I needed that.’

The next thing I work on: ‘Does my horse know where the end of the line is?’

I ask with slow movement and deliberation. You don’t want to be a big ‘ol jerk on the other end of the line here. The horses’ innate behavior is to run from danger, run from the predator, run through the end of the lead line. When a horse gets straight and strong and running for its life, best of luck holding on! It is totally acceptable to let go and start over again. Don’t beat yourself up. Just start over again and learn from what is and isn’t working.

I help my horse follow the feel of my energy and my intention. Can I gain the horse’s interest? Maybe it’ll take some wild, big-framed jumping jacks. This will surely get his attention. But I don’t want to scare him off. We’re trying to peak the horse’s curiosity with as little effort as possible.

The horse on the other end of the line is saying, ‘What the heck is that?!’ which translates to two eyes and two ears on you.

Gather up your lead line again, ask yourself:

- Can your horse follow a feel from your hand through the line to tip the nose with relaxation for the hindquarters to swing through?

- Can you push the life out of the horse’s feet while they are in movement?

- Can you direct the part of the horse you want to move, FIRST through a focus of energy and SECOND with our tools (the lead line, the flag, the smooch, the click) all in increasing phases of discomfort?

In my learning and teaching, I refer to this as ‘Pressing Through Intent.’ Can you look at the hindquarter and have your horse tip his ear, eye, and nose to you and then swing the hindquarter through? Think of this focused look, with soulful energy and initiation of this press, before you move your feet or lift up a feel on your line or flag. You want to keep slack in the line as long as you can, looking for the horse to pick you up with his eye or ear, before you bring any energy to an aid.

It’s simple but it’s not easy.

And it’s amazing how intriguing we humans can become to the horse when we practice these subtleties.

Don’t forget:

The horse must prepare to initiate a hoof lift by loading up weight in another hoof. Can you get in time with it and then release on the slightest preparation and try from the horse?

Intent should be focused on the part of the horse that I want to move. When I seek two ears and two eyes, and when the horse successfully turns and faces me, I immediately request a straight back up, consistently using a ‘how little can I do to get the slightest try’ approach. I don’t want the horse to engage through the hindquarters at this stage. I want physical and mental disengagement to help them cope with innate instinctual prey fears, on their own, at the end of the line, away from me.

I allow them lots of time to process. Again, chewing, blowing, yawning, head-shaking in conjunction with lip-licking and eye-blinking are all signs of the horse releasing its fear and getting a nice dose of the good learning-thinking chemistry.

This is not cookie cutter stuff, but it’s critical for your safety and connection. It’s through our mistakes and experimentation that we find the best learning in our horsemanship. Observe well and listen carefully to the best teachers in your studies, the horses.