Editor’s Note: Best Horse Practices Summit presenter Katrin Silva grew up riding dressage in Germany before moving to the United States at age 19 to learn to ride Western. She’s been riding both disciplines for the last 20 years and is a regular guest columnist for Cayuse Communications. The author of Dressage for All of Us: How to Help Any Horse Become a Happier, More Responsive Riding Partner lives in New Mexico where she works with dressage and Western clients.

Katrin’s upcoming book is Feel for All of Us, due in early 2022. Read more about that here.

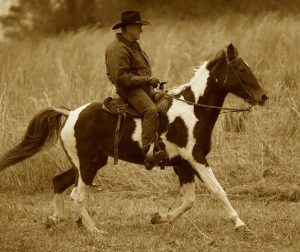

Katrin Silva at the 2019 Summit. Photo by Nina Fuller

Katrin writes:

I am a horse trainer. There is nothing I’d rather be, but I know that the profession is not a well-respected one. Horse trainers don’t have to take the Hippocratic oath before we test our skills on real horses. There is no college degree or board exam. If you want to call yourself a trainer, you can. If people pay you money to work with their horses, you are a professional.

The ethical slope can be slippery.

It would be easy to deny it or to blame a few bad apples. It would be easy to point to all the hard-working, honest colleagues I know. But I’ve also met horse trainers who use draw reins, illegal bits, and other cruel contraptions, especially when the horse’s owner is not watching. I’ve been around horse trainers who take a client’s money for 30 days of training, then work with the horse once a week, if at all. Trainers pressure clients into selling one horse and buying another, more expensive one, for no other reason than the trainer earning a large commission.

These pros did not start out treating their horses or clients so badly. They became horse trainers because they genuinely loved horses and want to make a living working with them.

These pros did not start out treating their horses or clients so badly. They became horse trainers because they genuinely loved horses and want to make a living working with them.

So, what has gone wrong along the way?

Sometimes, a young professional’s good intentions are derailed early on in her career. Many of us remember when, young and full of idealism, we rolled up our sleeves and paid our dues as assistant trainers or working students. We also remember the disillusion when we quickly figured out that the big-time trainer we idolized and felt lucky to work for was demanding and not nearly as charming as we thought. We found out that horse shows can be brutal once we looked beneath the veneer of white fences, fancy barns, and gleaming tack. We learned that polished performances have an ugly flip side.

I apprenticed with a well-known Quarter Horse trainer in my early twenties and remember the shock of seeing horses left standing in the arena with their heads tied to their tails, a tack room full of thin twisted-wire bits, and a barn refrigerator filled with bottles of Acepromazine.

Many aspiring horse trainers see no alternative to either adapting or walking away. They feel like they need to sink or swim. They learn to play the game that they think they need to play. I was fortunate to eventually meet other, better role models who genuinely care about the horses they work with. Once I was on my own, I found clients who put their horses’ best interests above their desire to win. Not all young trainers are this lucky.

Many aspiring horse trainers see no alternative to either adapting or walking away. They feel like they need to sink or swim. They learn to play the game that they think they need to play. I was fortunate to eventually meet other, better role models who genuinely care about the horses they work with. Once I was on my own, I found clients who put their horses’ best interests above their desire to win. Not all young trainers are this lucky.

Other times, the shift to unethical practices happens later. Many older horse trainers feel physically exhausted, financially strapped, and emotionally frazzled. Long hours for low pay and injuries are occupational hazards. Trainers end up feeling trapped in their careers, stuck in a profession they no longer enjoy or care about.

The Quarter Horse trainer I apprenticed with once told me: “If I knew how to do anything else, I’d do it. But training horses is all I’ve ever learned. Doesn’t mean I have to like it, or like horses.” Horses are the victims of this kind of burnout.

Whose fault is this? There are trainers who should not work with horses. Horse owners bear some responsibility, too, because they helped create a situation that puts a lot of pressure on professional trainers.

I’ve dealt with overly-demanding and unrealistic clients:

I’ve dealt with overly-demanding and unrealistic clients:

• people who expect me to work with their horses for free because they see me enjoy my job

• people who want quick results at the expense of their horse’s mental or physical welfare

• people who don’t see their own role in their horses’ behavioral problems and blame me instead

Thankfully, my current clients are people who love their horses, respect what I do, and genuinely want to learn. My barn is a happy place. I love my work, and I still ride horses all day because there’s nothing I’d rather do. I am surrounded by supportive colleagues with similar professional ethics and training philosophies.

But I know the training world is rife with concerns: How can we make the horse world a more ethical place? How can we establish a standard of professional conduct across the entire range of equestrian pursuits and disciplines? How can we keep trainers from falling out of love with their profession? Let’s acknowledge these problems and look for ways to improve, for the sake of our horses.

Well written, for the love of the horse. Thank you, Katrin. Kyla

Thank you, Kyla.

Well said. Support is the basis of evading burn-out, both personally and professionally. When we are able to find the right people such as trainers like you, we can change the culture, for people and horses.

Mary Ellen, support is key. I think all the envy, mistrust, and back-stabbing among professionals contributes to the high burnout rate. It’s time to change that.