Teaching/Learning is a two-way street

Editor’s Note: 2018 Best Horse Practices Summit presenter Katrin Silva grew up riding dressage in Germany before moving to the United States at age 19 to learn to ride Western. She’s been riding both disciplines for the last twenty years and is a regular guest columnist for Cayuse Communications. She lives in New Mexico where she works with dressage and Western clients. Visit her blog here.

Silva writes:

“Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.” Paulo Freire

Freire was a Brazilian philosopher and educator who wrote about two models of education:

The banking model: students are passive receptacles. Their brains are empty jars. The teacher alone possesses the commodity of knowledge, which she can stuff into the students until they’re full.

Problem-posing model: learning is a form of communication, a dialogue between teacher and student. Knowledge happens when dots connect, when problems are solved.

The two models have very different goals. The banking model fosters an attitude of unquestioning obedience, of meek submission. Problem-posing education is transformative. It empowers students, teaching them how to solve problems and to think critically.

The two models have very different goals. The banking model fosters an attitude of unquestioning obedience, of meek submission. Problem-posing education is transformative. It empowers students, teaching them how to solve problems and to think critically.

Freire’s theories have been around for almost fifty years, but problem-posing, transformative education has not penetrated much of the equestrian universe.

From personal observation and experience, I know that the banking model is alive and well here. Riding instruction too often consists of commands that students are expected to obey without questioning the “Why?” behind the imperatives.

When a student does ask “Why?” the answer is often “because we’ve always done it this way.” Or, “because dressage master X, or Olympic champion Y, or Natural horsemanship icon Z says so.”

But a good student wants to know more: “Why have we always done it this way?” or: “Why does Champion X do it?”

Anja Beran, one of my role models

Traditions deserve a degree of respect because unlike fads and fashions, they have stood the test of time. To gain perspective, we should all read Xenophon, De La Guerinière, Udo Bürger, along with the wise words of the Dorrance brothers. We can appreciate how much dedication, passion, and thought these people dedicated to the pursuit of better horsemanship. But reading these books also makes us realize that they often disagreed. Good riding is not just just one set of fixed rules – it’s an evolving idea, an elusive concept which shifts with historic context and cultural factors.

Had he been a horseman, Freire would have said that better horse-human connections evolve because of those disagreements, not in spite of them. There are so many new questions, new studies, new products. The quest for good horsemanship continues to evolve, which makes asking “Why?” even more important.

Along with the consideration of traditions, it’s also important to have role models –trainers whose methods we admire, whose technique and dedication serve as good examples.

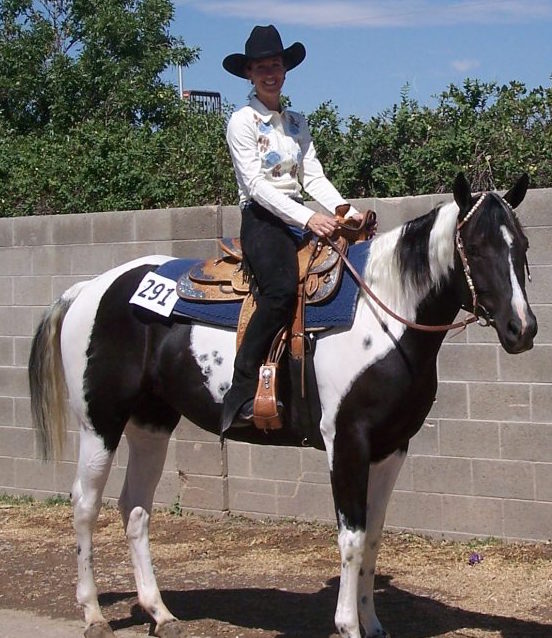

No, my Western Pleasure horses never dragged their noses on the ground.

As with traditions, we also need to ask them why.

- Why should we try to sit on a horse like they do?

- Why we should do what they do in the warm-up pen?

- Why we should use the kind of tack we see them use?

Imitation can be a useful tool. But imitation without understanding of Why becomes meaningless, or worse, destructive, as in the case of the infamous peanut roller craze in the western pleasure classes of the 1990’s. (No, my Western Pleasure horses never dragged their noses on the ground.)

When a student asks me a question that starts with “Why?,” I often respond with: “Let me think about this for a second.”

Sometimes, the answer is relatively easy: because this will help the horse become his best self over time: more relaxed, more supple, straighter, more balanced.

The answer is not always obvious, which is why I tend to think about it, or consult one of my books, or talk to one of my mentors. Other times, I can’t find a good enough answer and have to revise my methods. When I find that I subconsciously have imitated others without questioning, I go back and tweak what I do.

For example, I used to use flash nosebands on all my dressage horses, until a student asked me why. The honest answer would have been: “Because everyone in the dressage barn where I board my training horses uses a flash noseband, and I would like to fit in better!” Now, I rarely use a flash, and never without a valid reason.

We are learning to trust and respect each other: OTTB Ivy, at her first schooling show after two months of training.

There’s another reason to change riding instruction from a banking model to a problem-posing model:

Students who take lessons in a atmosphere of unquestioning obedience tend to expect a similar degree of blind obedience from their horses. But horses don’t think like humans. Good training involves encouragement and trust. Good training is a dialogue, a process of understanding the feedback the horse gives, and of choosing wisely how to respond. Or, in Freire’s words: “Whoever teaches learns in the act of teaching, and whoever learns teaches in the act of learning.”

So, I will ask you, Dear Reader, a question: Why can’t education in the world of horses be transformative instead of authoritarian?