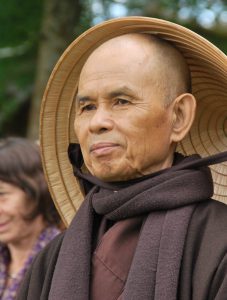

Thich Nhat Hanh

Editor’s Note: Thich Nhat Hanh was a Zen Buddhist master, author, poet, and teacher who helped pioneer the concept of mindfulness in the West. He died in Vietnam last month at the age of 95.

Writer Curtis Moore grew up in Bishop, California, where he spent his summers packing mules in the Eastern Sierra. During college, he cowboyed at a ranch near Greenfield, California, where he learned and practiced low pressure stockmanship techniques. In law school, he focused on environmental and natural resource law, subjects that would lead him to simultaneously pursue a master’s in conflict and dispute resolution from the University of Oregon.

Since graduating, he has worked as a law clerk in Ely, Nevada, a deputy district attorney in Elko, Nevada, and an adjunct political science instructor at Great Basin College, before becoming Elko County’s Natural Resources Director. He has published articles on scientific mediation in natural resource conflicts.

In his spare time Curtis rides his horse, Rooster, writes, and makes memes about underrated fantasy novels.

By Curtis Moore

Fear is about despair. It’s about looking into the darkness and not seeing.

This quote from Buck Brannaman is one of my favorites from his 7 Clinics DVD. In this same segment he compares fear to an animal, and explains that the only way to kill fear is with knowledge. “Imagine what it would be like, to honestly say in your heart that there is not a horse alive you are afraid of… Imagine what a relief that is.”

The idea that knowledge makes you a better horseman isn’t unique to Buck. Nick Dowers explains on his website: “I need to know what to do, when to do it, and why to do it. That’s everything.” And Buck’s insight on fear and horsemanship isn’t even a modern one. Edward I of Portugal wrote The Royal Book of Jousting, Horsemanship, and Knightly Combat in the 15th century, and he dedicated an entire section of this book to being fearless. He writes that “… those who have the knowledge and are aware of the existing dangers, either because they know them by experience or because they were taught will be, under God, protected from disasters; … they will have the appropriate audacity in some situations and fear and prudence in others.”

The idea that knowledge makes you a better horseman isn’t unique to Buck. Nick Dowers explains on his website: “I need to know what to do, when to do it, and why to do it. That’s everything.” And Buck’s insight on fear and horsemanship isn’t even a modern one. Edward I of Portugal wrote The Royal Book of Jousting, Horsemanship, and Knightly Combat in the 15th century, and he dedicated an entire section of this book to being fearless. He writes that “… those who have the knowledge and are aware of the existing dangers, either because they know them by experience or because they were taught will be, under God, protected from disasters; … they will have the appropriate audacity in some situations and fear and prudence in others.”

Not long ago I read another passage with a similar, but more broadly-applicable sentiment. “Our greatest fear is that when we die we will become nothing…. When we understand that we cannot be destroyed, we are liberated from fear. It is a great relief.” This quote comes from Thich Nhat Hanh’s book No Death, No Fear. It is a meditation on what fear is, where it comes from, and Nhat Hanh’s solution to it.

I started this article almost a year ago, so it is with some sadness that I had to change the title to Thich Nhat Hanh was an Excellent Horseman. I don’t mean this literally. No biographies that accompany works by the Vietnamese Zen master mention a passion for horses. What I mean is, the ideas found in Thich Nhat Hanh’s brand of mindfulness sound an awful lot like modern horsemanship, and there’s utility in that even outside the round pen.

When I first encountered his work in pursuit of a degree in Conflict Resolution, I had no intention of applying anything I learned to my horsemanship practice. I was learning mediation and negotiation skills, and mindfulness was presented as a way to be present in high-stress situations without becoming embroiled in the conflict. Nhat Hanh’s writings describe his experiences during the Vietnam War, where he and other monks were targeted by both sides because they refused to take sides. In Being Peace he writes, “[w]e shall learn and practice nonattachment from views in order to be open to others’ insights and experiences. We are aware that the knowledge we presently possess is not changeless, absolute truth.”

When I first encountered his work in pursuit of a degree in Conflict Resolution, I had no intention of applying anything I learned to my horsemanship practice. I was learning mediation and negotiation skills, and mindfulness was presented as a way to be present in high-stress situations without becoming embroiled in the conflict. Nhat Hanh’s writings describe his experiences during the Vietnam War, where he and other monks were targeted by both sides because they refused to take sides. In Being Peace he writes, “[w]e shall learn and practice nonattachment from views in order to be open to others’ insights and experiences. We are aware that the knowledge we presently possess is not changeless, absolute truth.”

Thich Nhat Hanh’s writing is filled with these kinds of passages. Though the language is simple, it has a way of percolating in your mind and popping up in odd places. That’s why I don’t have a clear memory of when I started practicing mindfulness when working with horses, or when I started to make the connection between his ideas and the horsemen I’ve long admired. But I have, and it’s made me a more present and better horseman.

As far as practical advice for horsemanship, I don’t have any insights to add that horsemen across centuries haven’t articulated more clearly and from a place of greater experience. However, horsemanship doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Until recently, horsemanship has always been a means to achieve an end, whether that end is connected with stockmanship, traveling, or combat. It’s been a skill meant to help us achieve a greater end.

Similarly, Thich Nhat Hanh’s writing on mindfulness isn’t an invitation to withdraw from the world and remain unaffected by it. The point of mindfulness is to put yourself in a position to have a larger impact on the world than you would be able to otherwise. “Our daily lives,” he writes in Being Peace, “the way we drink, what we eat, have to do with the world’s political situation. Meditation is to see deeply into things, to see how we can change, how we transform our situation.”

*******

Joel Nelson, pc: Lubbock Avalanche Journal

Rumor runs he nursed on mare’s milk, Some say he’s into Zen.

Truth is he lives and breathes his work. The breaker in the pen. – Joel Nelson, The Breaker in the Pen

Being present, being mindful, and increasing our knowledge are all goals we have as horsemen. At a minimum, learning and practicing mindfulness as envisioned by Thich Nhat Hanh may give us some tools to make us better riders. It’s also been my experience that skills I’ve learned around horses have helped me in my mindfulness practice. Once you’ve been through a few wrecks with draft mules, mediating even a tense small claims case doesn’t trigger the same fight-or-flight response it might otherwise. Because of what he taught me, I am confident in saying that, if he’d ever set his mind to it, Thich Nhat Hanh was an excellent horseman.

The first mindfulness training is important to help us remain free people. Freedom is above all else freedom from our own notions and concepts. If we get caught in our notions and concepts, we can make ourselves suffer and we can also make those we love suffer. – from Nhat Hanh’s book, No Death, No Fear: Comforting Wisdom for Life.

Dear Curtis, thank you for an excellent piece of insight. Mindfulness is an essential part of really good horsemanship, in any saddle, in any riding tradition. The horses themselves teach us how to be in the here and now if we listen, but most of us also need the guidance of a great teacher . Thich Nhat Hanh’s wisdom has guided my horsemanship for years. His words are so simple, yet so profound.

I love that you have brought mindfulness and meditation into your horsemanship. The teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh are a wonderful portal for us Westerners. However, your statement; “Until recently, horsemanship has always been a means to achieve an end…” should read; “Until recently, WESTERN horsemanship has always been a means to achieve an end…”. Classical riding has been thus evolved for centuries. Have a look at Nuno Oliveira, Alois Podhajsky, Dominique Barbier – there are many. It has been a beautiful thing that the western riding world has evolved in a way that is much kinder, gentler and more horse-centric Sadly, many in the western riding world see some of the Dressage riders and think that that is classical riding. Many of those in competition are horrific examples of what should be the highest level of communication with a horse. I started out in Little Britches Rodeo in the 1960’s so I’ve seen the worst and have watched it change – thankfully – but we mustn’t disregard history and those who truly paved the way.

Hi Janet,

I’ve read riding treatises from the Renaissance up through the Baroque period, and so I include those classical disciplines in my statement mostly because in the introductions to those treatises there’s almost always a section devoted to explaining to the reader why they should study horsemanship. So although those schools were not primarily focused on combat, traveling, or fox hunting, they present horsemanship as a means to make their students better at whatever they were going to do. This tradition extends back to Xenophon. So even if pursuing horsemanship for the sake of horsemanship is around 200 years old, the thousands of years preceding make it a relatively new phenomenon.

Thanks for letting me clarify my statement.

Wouldn’t it be nice if all horse training was thought of as meditation and non-violent communication and conflict resolution.