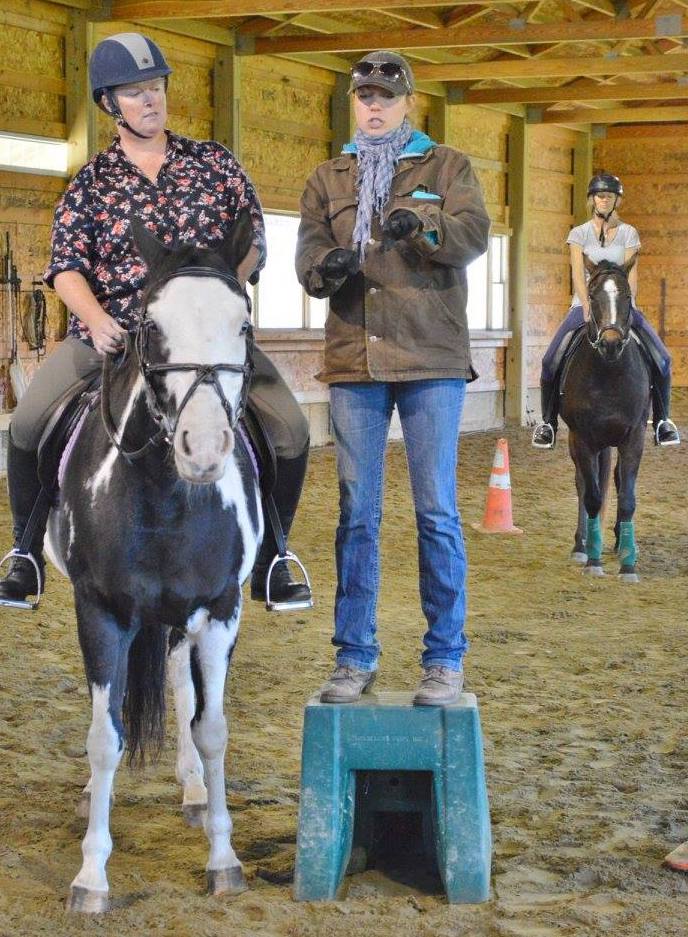

Amy Skinner at the BHPS 2018

Editor’s Note: Amy Skinner is a regular guest columnist and has been a horse gal since age six. She will present with fellow trainer and rider, Katrin Silva, at the Best Horse Practices Summit.

Skinner rides and teaches dressage and Western. Skinner has studied at the Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art in Spain, with Buck Brannaman, Leslie Desmond, Brent Graef, and many others. Visit Amy’s website here.

Skinner writes:

When I teach, I often ask students for their goals. Most people say they want a good relationship with their horse and a better partnership. As the lesson goes on, their frustrating problems creep up and we get down to nitty gritty, dealing with what happens when things don’t go the way they want.

I see fighting, temper flare-ups, frustration, name calling, and the use of force – and that’s just on the human side.

From our first encounter, we’re spoon fed this idea that we’re supposed to be the horse’s leader. Whether it’s worded “show ‘em who’s boss” or “be the leader,” the idea is the same. The human calls the shots and the horse obeys.

But many of the people looking to be the horses’ leader lack a real understanding of what the horse actually needs, or the education and timing to provide it. It’s like taking a kindergarten class and demanding you be the teacher of that class at the same time. You’re getting your bearings about you, learning your ABC’s but demanding the other kids listen to you while you teach them your half-learned alphabet song.

Sometimes in my lessons, the rider has totally misinterpreted the situation that frustrated them in the first place. For example, they think the horse is not listening to them when he won’t go, but actually the riders’ hands are blocking the horse from going. In that case, the horse was listening, and the rider was leading. But no points are scored in the relationship department.

Sometimes in my lessons, the rider has totally misinterpreted the situation that frustrated them in the first place. For example, they think the horse is not listening to them when he won’t go, but actually the riders’ hands are blocking the horse from going. In that case, the horse was listening, and the rider was leading. But no points are scored in the relationship department.

Or, the rider wants to lead, but doesn’t really have an idea of what they want. Years ago, I had a client who was was frustrated by her horse wandering off the trail and getting too close to the other horses on a trail ride. When I asked what she had planned to do about it, she said, “Well, I don’t really steer, I just try to enjoy the ride.”

How can you be a leader if you don’t provide input for the lead?

If it’s a partnership you want, it isn’t all about calling the shots. In a good partnership, there is give and take. Sometimes I lead the horse, sometimes I follow. To me, it’s an artful and delicate dance, where I try not to let the horse take over, but I listen to the horse and go with their needs in their time.

I think of good riding as I do teaching. When I teach lessons, I don’t demand a compliant response from my students. I don’t apply more pressure when they don’t comply.

This type of relationship doesn’t interest me because it doesn’t actually teach. Sure, I can get the satisfaction of having my ego stroked, but I didn’t create any real learning. What I want out of our student-teacher relationship is a thoughtful, engaged  dialogue. I offer feedback, direction and exercises to get to where the student wants to go. In turn, the student needs to engage, think, try things and essentially learn to feel their horse and try things because they understand the concepts, not just because I instructed them.

dialogue. I offer feedback, direction and exercises to get to where the student wants to go. In turn, the student needs to engage, think, try things and essentially learn to feel their horse and try things because they understand the concepts, not just because I instructed them.

When I work with young or troubled horses, there is leading in the sense that I offer direction and guidance. But it isn’t all about doing what I want. It’s about creating that same dialogue – a safe space where they’re free to try, to learn, and to let down enough for us to be on the same page. A young horse might offer to canter because they feel good. If I shut her down because it isn’t what I wanted, because I have to be the “leader,” I take away from our relationship. I’ve just proven to this horse that her efforts, her exuberance, her willingness is not appreciated.

Leadership means guiding – it doesn’t just mean making the horse do what you want, when you want it. If you can’t guide, what does the horse have to follow? Frustrations can arise because the horse won’t do what you want and she seems to take over. But it’s natural for a horse to take over when there isn’t enough guidance, or the guidance is poor or conflicts with the horses’ self interest.

A horse wants to feel secure and balanced. If you can’t provide that, he will look elsewhere. He’ll whinny or tune out. Do we have something worth listening to?

I don’t want a robot. I want a thinking, engaged partner. And a partner is someone who has input. They have some say in how things go. Need things to move slower? You got it, partner. Scared? I got your back. Frustrated? I’ll break it down for you.

Great blog, lot’s to think about, thanks Amy!!