Editor’s Note: Best Horse Practices Summit presenter Katrin Silva grew up riding dressage in Germany before moving to the United States at age 19 to learn to ride Western. She’s been riding both disciplines for the last 20 years and is a regular guest columnist for Cayuse Communications. The author of Dressage for All of Us: How to Help Any Horse Become a Happier, More Responsive Riding Partner lives in New Mexico where she works with dressage and Western clients.

Katrin’s upcoming book is Feel for All of Us, due in early 2022. Read more about that here.

Katrin Silva at the 2019 Summit. Photo by Nina Fuller

Katrin writes:

I think of good riding as having three main ingredients: a good seat, a lot of feel, and a coherent system of training based on solid theory. Good riders have a balanced, effective seat. Good riders are in tune with their horses. They have that quiet, elusive quality called feel (much more about this in my upcoming book, Feel for the Rest of Us). But, in addition, good riders are educated riders. While feel and a good seat will make it easy for you to get your horse to do what you’re asking, you must know what to ask for, and when, and why. You can’t help your horse become a balanced, happy athlete for the rest of his life without a thorough understanding of how to get there.

It is, of course, possible to teach a horse to respond to almost any set of cues:

- Western pleasure horses taught to do a spur stop, i.e. the harder you dig into their sides with rowel spurs, the slower they go.

- Gaited horses trained to go faster when their rider pulls straight back on both reins of a long-shanked curb bit.

- Dressage horses who feel like they would fall down without heavy, constant rein contact.

- Show horses who were warmed up in draw reins or tight martingales until five minutes before they enter the ring, in order to maintain the frame they were forced into long enough to survive and even win their class.

- Trail and endurance horses who have learned that the only way to slow down is a one-rein stop while ignoring their rider’s gripping legs or a bouncing seat.

These are dead-end ways of training. They may work for a while, for specific purposes in specific situations. They may even lead to some degree of competitive success, but they are not part of a larger riding tradition with the long-term goal of improving a horse’s long-term physical and mental well-being. They do nothing to even out a horse’s lateral or longitudinal balance. Eventually, dead-end methods lead to harsh corrections, mutual frustration, broken-down horses, and/or broken-down horse-rider relationships.

These are dead-end ways of training. They may work for a while, for specific purposes in specific situations. They may even lead to some degree of competitive success, but they are not part of a larger riding tradition with the long-term goal of improving a horse’s long-term physical and mental well-being. They do nothing to even out a horse’s lateral or longitudinal balance. Eventually, dead-end methods lead to harsh corrections, mutual frustration, broken-down horses, and/or broken-down horse-rider relationships.

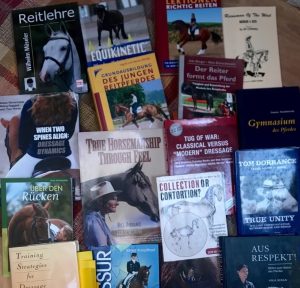

A coherent system of training, on the other hand, can help a horse develop into a more and more willing partner. A coherent system of training promotes longevity because it respects the horse’s physical and mental development while building the kind of muscles that make carrying a rider more comfortable. Classical dressage, ranch-type western riding, and working equitation, belong in this category. They all have important things in common: a long history, a body of theory, an evolution, and generations of master equestrians to serve as role models. All long-standing traditions of horsemanship have a lot more in common than most people realize. Which one you choose is ultimately less important than your willingness to learn.

But how do we learn? How can we avoid getting lost in the jungle of information about horses and horsemanship? It’s not as simple as repeating what someone else is saying. Educating ourselves means taking lessons, attending clinics, reading books, watching videos, watching other riders, critical thinking, recognizing the dead ends mentioned above, and asking lots of questions. It means finding trustworthy, knowledgeable mentors to guide us and to allow and encourage questions. It means examining and re-examining the answers we get. It means putting theory into practice on actual horses, because if it doesn’t work, we’ve either misunderstood it, or it’s faulty. Because of all this, education is not a simple, straightforward process. It’s complicated and messy.

But how do we learn? How can we avoid getting lost in the jungle of information about horses and horsemanship? It’s not as simple as repeating what someone else is saying. Educating ourselves means taking lessons, attending clinics, reading books, watching videos, watching other riders, critical thinking, recognizing the dead ends mentioned above, and asking lots of questions. It means finding trustworthy, knowledgeable mentors to guide us and to allow and encourage questions. It means examining and re-examining the answers we get. It means putting theory into practice on actual horses, because if it doesn’t work, we’ve either misunderstood it, or it’s faulty. Because of all this, education is not a simple, straightforward process. It’s complicated and messy.

To avoid the inevitable phases of confusion that are a part of any true learning experience, many of us feel tempted to choose and blindly follow a training method or a guru figure.

Don’t do it.

Silva conducts a clinic

It’s a shortcut and it won’t lead to lasting results. Above all, be wary of systems and methods named after a single person. Traditions of horsemanship take a lot more time to evolve than the few decades that make up one lifespan. True horsewomen and horsemen know this. Rather than claiming to have reinvented the wheel, they humbly acknowledge that they stand on the shoulders of those who came before them.

Lastly, a coherent system of training is never a cookie-cutter solution that fits all horses, all the time. Riding traditions are based on clear values and principles, but they still respect horses as individuals. A training system that has evolved over centuries is, by definition, not random. But it’s not dogma either. It can’t be, because horses are living beings, not robots with buttons we can push.

Good riders are sensitive to what their horse needs at any given moment. I respect the training scale of classical dressage, yet realize it is not set in stone. It’s a set of guidelines, with certain limits and exceptions. Its principles are valid for all horses, yet their exact interpretation varies from horse to horse, depending on conformation, training history, and temperament.

Are you confused yet?

I’ve been a student of horsemanship for almost 40 years, and I still get confused. There’s only one thing we can do: embrace the process, with all its loose ends and untidy edges. From there, we can look forward to moments of clarity that become more frequent over time. So, read books. Watch videos. Find a mentor, or two. Ask questions. Educate yourself. Your horse will thank you.