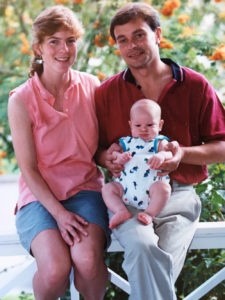

With our first son, 1991

My ex-husband – father to my three sons, an Irishman to whom I was married for 12 years – died this spring. He was estranged from us for over a decade.

Read follow-up to this essay here

The boys – now men in their 20’s and scattered across the country – came hurriedly to a Massachusetts hospital to say their goodbyes. After a lifetime of hard living, their father – once strong, athletic, and handsome – had submitted to self-inflicted disease. He had just turned 60.

A few weeks later, the four of us met in Maine. We shared old photos and went through his few possessions. We drank pints, sipped coffee, and commiserated in the full sense of the word. With hesitation, I agreed to take the ashes. They were too heavy a burden for my sons, I figured, and holding onto the remains wouldn’t unsettle me.

Gingerly, I placed the grey, lunch-box sized container in my carry-on and boarded the bus to Logan airport.

With a few hundred fellow travellers, I shuffled through security, taking off my shoes and pulling my laptop from my backpack. I stepped through the whole-body screening and waited for my gear. And waited.

A stocky man in a blue uniform pulled me aside. He looked back at the monitor and asked to unzip my carry-on. He reached for the grey, plastic box and asked, “what’s inside?”

A stocky man in a blue uniform pulled me aside. He looked back at the monitor and asked to unzip my carry-on. He reached for the grey, plastic box and asked, “what’s inside?”

“My ex-husband’s ashes.”

In the bottle-necked hustle and bustle of the security line, amidst strangers and federal officers, I started sobbing. Blood rushed to my head. My knees shook and weakened.

I watched as the TSA agent swabbed the container for explosives and ran a test with a machine. He consulted his supervisor and handed back the container. Dazed, I repacked and shuffled to my gate.

What had just happened?

Like the weekend luggage, I zipped up and carried on. I’d mourned the end of that relationship long ago. My TSA meltdown could be chalked up to fatigue and travel stress.

Days later, I was getting my hair cut by my friend, Angela, and I recounted the scene. Composed and unemotional, those airport tears now seemed distant and absurd. I laughed. But Angela said seriously, “he gave you a gift.” She felt that the moment presented an opportunity to flesh out my feelings and make better peace with the past.

As an American, as a Mainer, as a country girl, I grew up learning otherwise.

- Don’t cry.

- Rub some dirt on that cut and get on with your day.

- Chin up and soldier on.

As horse owners, especially, we learn to snub all sorts of pains. We learn to cope and move forward. Always forward. Death and pain are ordinary parts of rural lives with animals. We do what we can through compassion and care, but we do not dwell. A tough day is just a day. Rub some dirt on it and get on with things.

As horse owners, especially, we learn to snub all sorts of pains. We learn to cope and move forward. Always forward. Death and pain are ordinary parts of rural lives with animals. We do what we can through compassion and care, but we do not dwell. A tough day is just a day. Rub some dirt on it and get on with things.

This toughness paradigm works. Until it doesn’t.

Last week, I was reading West Taylor’s account of his work with veterans at Heroes and Horses in Montana. He said vets tend to cope until things blister and burst in the form of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Some get help. One former soldier cried as he worked with a mustang. Thanks to the program, he welcomed the new emotions as “one way that I know I’m alive,” he said.

I think all of us humans cope until we won’t. Or don’t. Or can’t. Eventually, coping cannot hide what ails you. It might be a teary meltdown in a public place. It might be an ulcer or back pain. It might be a relationship break-up or a job firing.

This year, with the help of friends*, good books*, songs*, and movies*, I’m seeing that “moving forward” isn’t about ignoring trouble and trauma. Rather, it’s about accepting the impact and trying to be open, vulnerable, humble, and aware. It’s a strange, new practice – especially since I thought I was already being open and aware. This quiet adjustment is, in turn, making me better with horses.

Consider these tasks:

- Haltering

- Riding and ponying horses to a new pasture

- Brushing manes and tails

- Trimming hooves

We’re works in progress.

In the past, these were git-er-done tasks. I moved through them with a focus on accomplishing the work.

Now, I pay more attention to the process. Git-er-done takes a backseat. Moments get broken down into micro-moments. The spinning world slows down. From an outsider’s perspective, I’m not taking any longer. The dogs are still milling on the other side of the fence. Horses have ears on me as I move around their space. Music might be playing from my phone.

But things feel different:

When I go to halter my new horse, he lifts his head. He’s had bad haltering experiences and is unsure of my intent. I could ignore it, but instead, we back up and I work to make him feel better about the experience. The new approach took five “extra” seconds.

The new horse doesn’t know about being ponied down the road with three other horses either. He doesn’t know about trotting for a mile as a group to get to better pasture.

In the past, I’d have him on a short lead line and would dally if he lagged, forcing him to keep up through pressure. If I failed to dally quickly, he’d have pulled the line from my hand and gotten loose. Either outcome was less than ideal.

Now, I give him an extra long lead line and we take our time moving away from the paddock. When we trot, he momentarily lags behind, unsure of the arrangement. I let the line out. As the other horses quicken (they know the routine and are motivated to get there), he pulls up even. In a few minutes, he’s hip to the walk-trot changes and seems happy with this new deal, even pleased with himself.

This horse and I, we’re works in progress. Successes are nice. But mistakes and meltdowns are golden. They reveal what has been skipped, neglected, or ignored. They remind me to live the journey.

Read follow-up to this essay here.

Footnotes (marked by **):

I owe special thanks to friends TJ Zark, Amy Skinner, and Warwick Schiller for their kind, helpful insights.

Thanks, too, to Brandi Carlisle and her brilliant song, “Every Time I Hear That Song”

These books have been pivotal in helping me gain new perspective:

“The Body Keeps the Score” by Dr. Bessel Van der Kolk

“On Grief and Grieving” by David Kessler and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

The movie, The Rider, showed me that sensitivity, courage, humility, and confidence can all live together in a person (and in a movie). A must-see film.

the moments we can chose to hold on to and the ones we let go. Thanks for sharing Maddy

I’m very sorry for your loss Maddy.

For me paying more attention to the process might take a little more time. It might be time to pet the barn cat who just rolled over for a belly rub, time to watch the herons and spoonbills in the shallows of the pasture lake, or time to scratch a horse in that special spot under her neck or his belly. That’s time that might have been sacrificed to get ‘er done in former days, but it’s precious time now.

Possible additions to your book list might be some by Thich Nhat Hanh like The Miracle of Mindfulness and The Art of Power.

Thank you Maddy. Great blog. You are truly a gem. Jules Horsewalker

Thanks Maddy for such a brave thought-full article. Will take the wisdom shared here , fold it up like a piece of origami and keep it tucked in my psyche’s pocket.

Will watch THE RIDER and offer in return either the non fiction book or movie made from it, TRACKS by Robyn Davidson. Camels instead of horses and a two thousand mile walk alone across the Australian out back.

Wow, beautiful article. Thank you for being vulnerable enough to share this story.

It’s a hard thing to say goodbye, whether to a person or memories of the past, no matter the circumstances.

You realize how much it all meant to you when you begin to grieve. And by grieving, you give this person – or

these memories – the honor they deserve. Because it is part of who you, yourself, have become. Thank you for your

generosity in describing your experiences. May each new day bring happiness and peace.

Beautifully written. Thanks for giving me a moment in my crazy day to reflect on what’s important. There aren’t enough of those….

Thanks for sharing your growth and some resources for us to dig into.

Thank you for sharing your journey and your great insight!!!