Curtis rides his mustang, Rooster

Editor’s Note: We welcome guest writer, Curtis Moore, as he remembers his horseman grandfather.

Moore grew up around horses and spent high-school summers at a pack station outside Bishop, California. During college, he worked on a ranch and adopted a sorrel mustang, When Moore headed to law school, the mustang, Rooster, came with him and has developed into a solid all-around ranch horse.

Moore is now an attorney and Natural Resources Director for Elko County, Nevada, where he lives with his wife and two young children. Read his contribution on Learning Schools and How to Avoid Tribalism here.

Moore writes:

The red horse trots easily in a circle, settling into the gait he can maintain for hours as he eats up miles. His name is Rooster, but my four-year old daughter calls him Grumblegard, after a particularly grumpy dragon on one of her Netflix shows. He looks even more dragon-like than usual today, with steam pouring from his widened nostrils. Those nostrils aren’t surprising. I haven’t ridden him since July. Life with work and kids gets busy, I tell myself. But moreso, it’s memories that have kept me away.

Heavens, back in the day.

Still, three months is a long time for a horse to go without work, so a little snortiness is to be expected.

Expected. That word brings a pang, though not the first of this day, as I remember my grandpa saying: “A horse will act just like you expect him to.”

It’s been over two months since he passed away and over three months since I went to Colorado to say goodbye. Now, in my memory, his voice comes through as clear as ever, focused and amplified by the boards of the round pen. It’s as if the one we spent so much time in was connected to this pen through time and space. I push it away, trying to focus on the horse, but my mind wanders anyway.

The tiny town of Hugo, on the eastern plains of Colorado, isn’t the sort of place I’d visit for fun, especially in July. First, there’s the potential for tornadoes and it’s not clear to me why anyone lives in a place where clouds can actually kill a person. Second, there’s more mosquitoes than anywhere I’ve ever been, except for Alaska.

But this trip wasn’t for pleasure. The only pleasurable thing about it was the tall whiskey my cousin poured me as we sat in the humidity of the front yard, avoiding the heat of the old house.

Moore’s father and grandfather lead a team.

Once we’re caught up on the doings of spouses, kids, chickens, and work, a long, comfortable silence stretches between us.

“Remember those damn ponies?” she finally says.

Of course, I remember the ponies. I was seven or eight when my dad and grandpa decided their path to success lay in a pony ring. One spring day Grandpa showed up with six ponies he’d picked up cheap, all loose-loaded in his stock trailer.

There was a reason those bastards were cheap. Likely, none of them had been touched. My cousin and I were the only kids big enough to ride a pony, but not too big. She tells me about the time Grandpa put her on one and it took off and threw her into a ditch.

“I didn’t ride a horse from then until I was in college,” she tells me.

I take a sip of whiskey. It burns, but it’s a pain you expect and can control to some extent, followed by a welcome numbness. “I didn’t know quitting was an option.”

That’s not strictly true. It’s more that it never occurred to me to ask. At that age, I didn’t want anything but to be a cowboy. I came off a few times despite the wide swells of my little saddle. Every time, Grandpa would dust me off, put my hat back on, and set me back on one of those beasts. I spent that whole summer working and riding those miserable ponies. I loved every minute of it.

In the round pen with Rooster, I stop him and gather the reins in my fist, a habit I learned the hard way after a pony took off as I was mounting. Shoving a boot in the stirrup, I swing up, and my grandfather’s voice echoes across the years again. Mount like you’ve got somewhere to be. Another lesson learned on another trip to the ground.

Rooster, or Grumblegard, as he’s called now, steps out and I point him out the gate and into the desert. A part of my mind recognizes that, after three months, I should probably spend some extra time in the round pen. But he doesn’t need it now. At least, I don’t expect him to, and that’s what makes the difference.

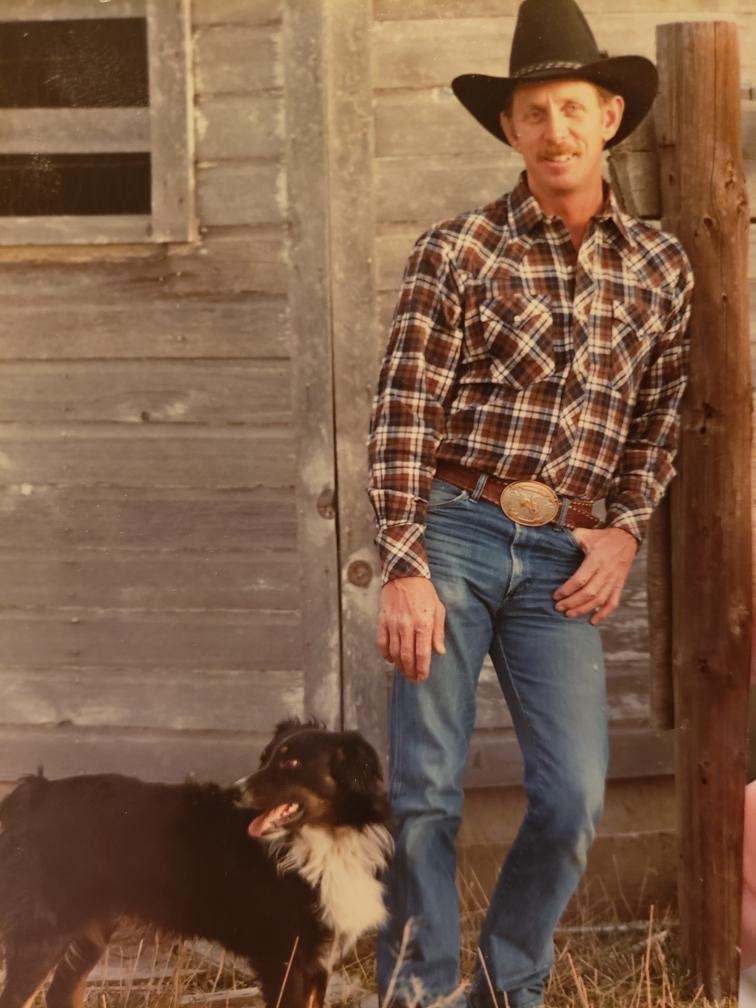

Curtis Moore in Elko

I love that concept…. it’s what you expect. Thanks for sharing.