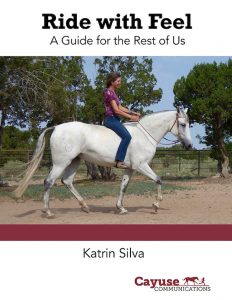

Editor’s Note: Best Horse Practices Summit presenter Katrin Silva grew up riding dressage in Germany before moving to the United States at age 19 to learn to ride Western. She’s been riding both disciplines for the last 20 years and is a regular guest columnist for Cayuse Communications. The author of Dressage for All of Us: How to Help Any Horse Become a Happier, More Responsive Riding Partner and the forthcoming Ride with Feel: A Guide for the Rest of Us lives in New Mexico where she works with dressage and Western clients.

Katrin Silva writes:

Some horses are born with choppy gaits that are hard to sit. Steep shoulders and straight hocks, backs that are disproportionately short or long, or a downhill build can make it challenging for a horse to carry a rider comfortably. Even horses born with smooth movement often learn to tense and brace their backs as a way to protect themselves from unbalanced or inconsiderate riders.

The good news:

With the right kind of work, every horse can become easier to sit over time. Stretching, bending, and leg-yielding will help ease any tension in the horse’s back. A relaxed, supple back is then ready for the kind of work that makes it stronger in the right places, like walk-canter-walk transitions and shoulder-in. This combination of yoga and weight training is the essence of dressage. Going back and forth between stretching and strength training builds a well-muscled yet rhythmically swinging topline, which makes it easy for horse and rider to connect and communicate. Sitting on such a horse is joyful. Sitting a horse whose back is weak or defensive will rattle the fillings from your teeth. Imagine how much worse it feels to the horse.

I used to be proud of being able to sit pretty much any horse’s gaits without bouncing. I thought it was part of my job to endure pogo-stick trots and washing-machine canters. The older, wiser me realizes what a dubious skill this is. Because of it, my back, and a lot of horses’ backs, took a beating over the years. Even if your core is strong and your seat is biomechanically correct, sitting deeply on a tense, weak, unbalanced horse won’t teach that horse how to improve the situation. At best, the horse learns to tolerate a familiar degree of discomfort. At worst, the horse’s back becomes even more tense, which creates a vicious cycle of increasing stress on both equine and human bodies.

I used to be proud of being able to sit pretty much any horse’s gaits without bouncing. I thought it was part of my job to endure pogo-stick trots and washing-machine canters. The older, wiser me realizes what a dubious skill this is. Because of it, my back, and a lot of horses’ backs, took a beating over the years. Even if your core is strong and your seat is biomechanically correct, sitting deeply on a tense, weak, unbalanced horse won’t teach that horse how to improve the situation. At best, the horse learns to tolerate a familiar degree of discomfort. At worst, the horse’s back becomes even more tense, which creates a vicious cycle of increasing stress on both equine and human bodies.

The older, wiser me will post the trot and take a lighter seat at the canter until the horse’s back invites me to sit, until it feels like I can sit in it, rather than on top of it. Posting the trot makes things more comfortable for both parties. It’s a compromise: we temporarily sacrifice some degree of feel and communication while we build relaxation and trust, or while the horse’s back muscles warm up early in the ride.

When is it time to start sitting? Only the horse can tell me. I will sit a few strides at a time, conscious of any changes in tempo or rhythm, of any tension creeping in. At first, I will sit before and after transitions, making sure that my back is soft and following, not interfering with the horse’s movement.

Before I can use my seat as an aid – before the horse goes how my seat suggests – my seat is passive rather than active. It’s a version of the Ray Hunt saying: “First, you go with them. Then they go with you. In the end, you go together.”

Before I can use my seat as an aid – before the horse goes how my seat suggests – my seat is passive rather than active. It’s a version of the Ray Hunt saying: “First, you go with them. Then they go with you. In the end, you go together.”

There are times when posting or taking a two-point are not the best option on young or tense horses, for safety reasons. But when I do sit on young or tense horses, it’s a different picture from a full dressage seat. I keep more weight in the stirrups and down my thighs, almost hovering. The deep dressage seat, with most of my weight on my two seat bones, develops gradually from this young-horse seat, as the horse’s back and mine develop a trusting, mutually respectful relationship.

A green or tense horse’s back and I are like two people who just started dating. We have to spend time together and make small talk before we commit to a long-term, consensual relationship. Sitting deeply on a weak or tense back is like proposing marriage on a first date. There is a time and a place to do it, but doing it too soon will almost certainly ruin an otherwise promising romance. It’s much better to get to know each other first.

One more thing to think about: there is a big difference between a trot that’s easy to sit because the horse’s back is swinging, and a trot that’s easy to sit because the horse is holding his back in a rigid position, moving only his legs. In the latter situation, movement won’t go through his entire body. This often happens to horses who have been ridden in draw reins or tie downs. While their gaits are easy to sit, there is nothing joyful about the experience.

The difference between good smooth and bad smooth is like the difference between a ripe tomato just harvested from a lovingly tended garden, and a hothouse tomato found in the supermarket produce section in mid-January. The supermarket version may look perfect from the outside, but once you bite into it, there’s no comparison to the former. Once a rider has experienced a truly relaxed, strong, swinging trot and a truly round, rhythmic, cadenced canter, no substitute will do. It’s worth the time and effort it takes to develop it – for the horse’s sake, and for ours.