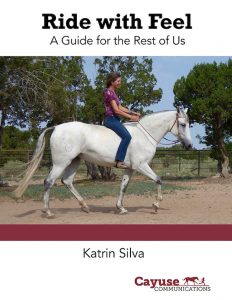

Silva’s forthcoming book

Editor’s Note: Best Horse Practices Summit presenter Katrin Silva grew up riding dressage in Germany before moving to the United States at age 19 to learn to ride Western. She’s been riding both disciplines for the last 20 years and is a regular guest columnist for Cayuse Communications. The author of Dressage for All of Us: How to Help Any Horse Become a Happier, More Responsive Riding Partner and the forthcoming Ride with Feel: A Guide for the Rest of Us lives in New Mexico where she works with dressage and Western clients.

Katrin writes:

Twelve years ago, I started running ultramarathons. I had just turned 40 and was suffering from a severe midlife crisis. In addition to signing up for the Leadville 100, I made some other rash decisions, like going back to graduate school and quitting horses. Thankfully, the “quitting horses” part only lasted a few months. The grad school part lasted until I had finished my somewhat irrelevant thesis on postcolonial literature. But On the running has endured lasted and shows no signs of fading. Having finished twenty 100-mile races, I can honestly say that running ultras has changed my life for the better. It’s made me healthier, happier, and stronger. Only recently have I realized it’s also made me a better horsewoman.

Katrin won her age group at the recent Big Horn 100 in Wyoming

When I ran my first Western States 100, which follows the same course as the Tevis Cup endurance ride, I was surprised to learn that the finishing times for horses and humans are very similar for both races. We are very different animals in most regards, but endurance is a superpower we share. Horses and people can run 100 miles at a steady pace without a break; most other animals can’t.

For different reasons, both species evolved to be on the move most of the time. My own endurance training has helped me understand on a gut level how important it is for horses to keep moving, how keeping them locked in a stall most of the time is the worst thing we can do for them. The secret to a more cooperative horse is often just more exercise – under saddle, in hand, on a lunge line, turned out with other horses, all of the above, every day, most of the day. Many behavioral problems have a simple remedy: get the horse moving forward. I imagine the crabbiness and unease I feel when I sit around too much must be what horses feel when we force them to be idle.

Running 100s has also taught me to enjoy the process of training, independent from the final outcome. In my twenties and early thirties, I used to train horses with a focus on a goal – usually doing well at a show or moving up to the next level of dressage. With green horses, my main goal was checking off the list of things I felt they needed to know before they could go home to their owners.

When I started running ultras, I started to recalibrate my focus from goals and outcomes to the joy of being, of running. When you train for a 100-mile run, you spend a ton of time moving forward at a pretty easy pace. The goal of finishing the race and earning a silver belt buckle can add motivation, but that distant promise of fleeting glory won’t provide enough incentive to get you out on the trail day after day, hour after hour. Instead, running becomes part of who you are, something essential to your very being.

When I started running ultras, I started to recalibrate my focus from goals and outcomes to the joy of being, of running. When you train for a 100-mile run, you spend a ton of time moving forward at a pretty easy pace. The goal of finishing the race and earning a silver belt buckle can add motivation, but that distant promise of fleeting glory won’t provide enough incentive to get you out on the trail day after day, hour after hour. Instead, running becomes part of who you are, something essential to your very being.

I now realize I feel the same about horses. They are a part of me, so the time I spend with them is never wasted, whether it’s riding, ground work, grooming, barn chores, or just being around them. I still have goals, but winning ribbons now matters much less than the joy I find in my daily work, my daily connection with these amazing creatures.

The most important ultra lesson: a good mindset is more important than physical talent. Running these races is at least 50 percent mental tenacity.I am not a natural athlete, yet I’ve had success in tough races. Working with horses has given me this grit and discipline. As I get older, I realize training their minds is at least as important as developing their muscles.

If I can get a horse to want to do what I’m asking, the training process won’t be a struggle involving a winner and a loser, but a willing partnership. If I can engage a horse’s mind in a positive way, his physical limitations might matter a lot less.

If I can get a horse to want to do what I’m asking, the training process won’t be a struggle involving a winner and a loser, but a willing partnership. If I can engage a horse’s mind in a positive way, his physical limitations might matter a lot less.

How do I engage a horse’s mind?

- By being just like I want the horse to be: calm, respectful, confident, consistent.

- By challenging each horse to move one step beyond his current comfort zone.

- By recognizing signs of boredom, anxiety, or frustration, and adjusting what what I do with the horse’s feedback.

- By rewarding often.

- By quitting every session on a good note.

Running lots of miles makes me ride better, and riding lots of horses makes me run better. It’s a strange combination, but it works for me.

Inspiring read!

Congrats, Katrin!